Many years ago, when I first entered into the world of duplicate and tournament bridge, it became quickly apparent that the opportunities for my advancement, and that of other women in our circles, were much fewer than those of our male peers.

Op-ed by Jude Goodwin

Childcare posed a constant challenge. Finances often made things difficult (men earn more than women and are typically more free to earn). Travel to and from tournaments could be daunting for single women. Accommodation choices were limited for women (where groups of men could share a hotel room, it wasn't appropriate for a women to bunk in; where men could book cheaper rooms a distance from the playing site, it wasn't safe for women to be walking to and from on their own, etc). And society itself discouraged women from leaving their children and homes just to go out and play a game. In short, bridge was a man's game. On top of that, I was denied the opportunity to play with some of the better male players when their wives (or my husband) complained.

In my case, it became easier to simply stay home and not pursue any kind of career at the bridge table.

The subject of women's bridge is not a new one. Women's events, for example, have been questioned. Why do we need them? Do they discriminate? I've always maintained that women's bridge is entirely about access. It gives women access to aspects of the game they would be denied in open events. Access to earning masterpoints. Access to earning recognition. Access to funding. And access to participation itself - tell your family you're flying to Italy to participate in the Women's Team Championships and there may be a modicum of support. Women's events are encouraged in a patriarchal society - they keep women in their place - ie with other women. And they keep women from wanting to encroach on men's spaces - ie the open events.

The biggest hurdle for women in bridge (and elsewhere in society) has always been the language used to keep these structures in place. None of the issues I touched on in my opening paragraphs were ever addressed. What was addressed and discussed over and over was the question of whether women, as a whole, could ever be as good as men at the game. Were their brains (and hormones) simply not wired for bridge? Fast forward to 2022 and we have a term new to the debate: Neurosexism.

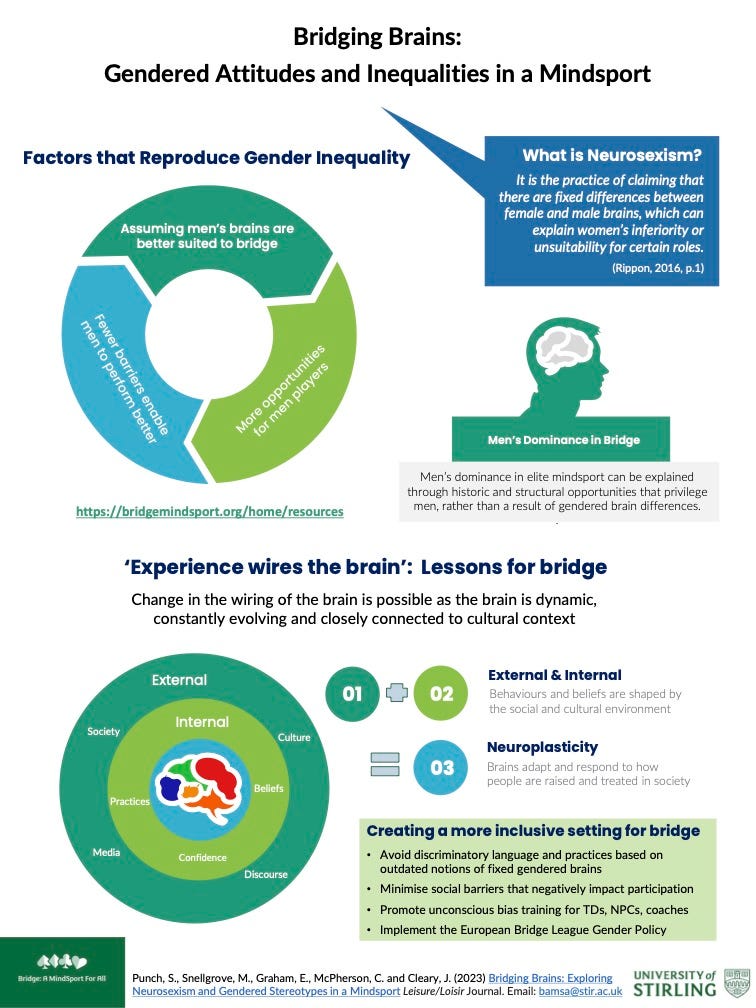

In a recent paper by BAMSA (Bridge: A MindSport for All) it is argued that gender stereotypes and neurosexism can actively reproduce inequality within the game to the detriment of women bridge players.

Samantha Punch on Bridge Winners writes : Rippon defines neurosexism as "the practice of claiming that there are fixed differences between female and male brains, which can explain women's inferiority or unsuitability for certain roles" (Rippon, 2016, p.1). Both men and women players may inadvertently engage in casual sexism and discriminatory language regarding the aptitudes and abilities of women players.

Neurosexist discourses, whether intentional or not, create social barriers that have negative consequences on girls' and women's participation and inclusion in bridge. The paper argues that men's dominance at the top of bridge can be explained through historic and structural opportunities that privilege men rather than gendered brain differences.

You can read this paper here: Bridging brains: exploring neurosexism and gendered stereotypes in a mindsport.

The idea that women's brains are somehow less capable at the bridge table than men is ridiculous and the paper linked above makes some excellent points int its discussion of how women are 'socialized from an early age into culturally appropriate gendered behaviours'.

Girls and boys are educated, formally and informally, in very different ways (Talbot, 2017), with competition, sports and aggressive mentalities on ‘winning’ considerably more likely to be emphasized in a boy’s childhood rather than a girl’s. For example, male and female champions of bridge argued that the problem is ‘that young girls are not trained to be as aggressive and competitive in the warlike atmosphere of big-time duplicate bridge’ (Smith, 1987). Men have long been rewarded for ruthlessness, competitiveness and aggression, whilst women are punished as being ‘deviant’ for displaying the same qualities (Niederle & Vesterlund, 2007).

This paper is a good launch point for resolving inequities in bridge. But where do we go from here? Short of dismantling the patriarchy completely, there are many ways to promote equity for women in the game of bridge. Addressing neurosexism in bridge through an examination of language is a great first step and could easily be added to discourse around learning the game as well as training for the game (admin, directors, etc). This would require close examination of all print material used by NCBOs and bridge educators.

BAMSA has put forward their suggestions - see the graphic below. I'd like to suggest more practical steps that could be taken.

Lower fees and entry for women, regardless of event.

Travel grants and support for women, regardless of event.

Possibly move to deconstruct the idea of 'women's bridge events' altogether

A continuation and support for on-site childcare where possible.

Mandatory mixer events at lower levels (clubs, units) to remove barriers for women and men playing together

More Mixed events at all levels to normalize women and men playing together.

I'm not a fan of the term 'equal opportunity' - women are not seeking equal opportunity so much as equity - barriers for women in bridge are different than those for men. Equity means removing the barriers completely.

And finally, let's 'call out' oppressive language! Let's call out neurosexist language. Using language that implies women aren't as smart or as capable as men is a tool of oppression. Full stop.